I used to find it strange when someone mentioned they had “hit a wall.” I always thought it was easy to monitor how much you work. If you think you’re working too hard, you can simply work less, right?

However, after reading Niklas Nygren’s post, everything made sense.

“I am 43 years old, married, and have two children. I am a specialist in psychiatry and work as a senior physician in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. I am sick because, one day, my brain decided it had had enough. Our efficient cooperation ended on a beautiful day in May. ‘Ended’ is perhaps a bit dramatic, but I could no longer do my job. I sat in my chair and had a ‘short circuit’ in my brain, as a psychologist put it.

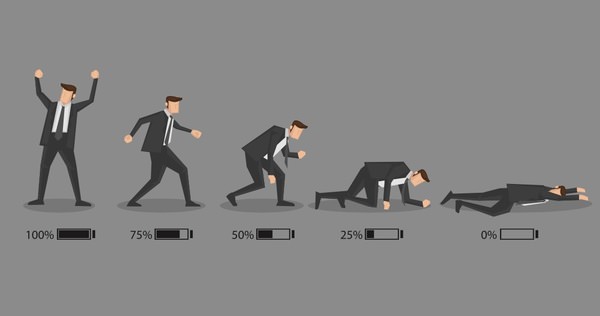

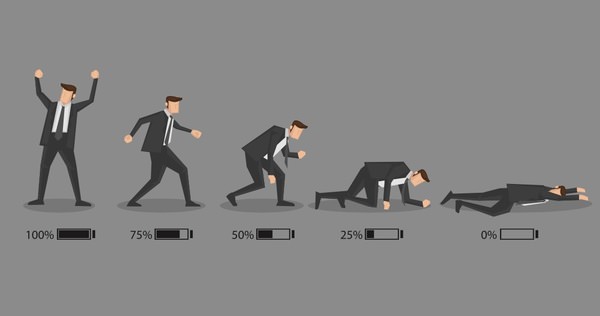

Burnout. There are many studies and many good articles available on this subject. But ultimately, it all comes down to this: Our brains are designed for short periods of stress. We can get a lot done in these periods. Stress acts as a kind of turbo or overheating for our brain. It is a good, purposeful system that helps us function and react quickly when under pressure. But this system is not modern. It is older than humans in our current form and is similar to systems typically found in animals.”

“It is necessary to have a balance to optimize our brain and stress system. After a period of overheating, the system needs to be turned off, cooled down, and recover. That sounds reasonable, right? But what happens if that doesn’t happen? Current research shows that stress, and more specifically, stress hormones, have a corrosive effect on the brain. If nerves constantly ‘bite’ the brain, stress hormones cause them to shrink. Nerve endings retract, creating space between different nerves.

The signals are no longer transmitted as they should be. It’s a bit like a phone network with poor signal. Conversations drop out, and the quality is poor. It causes the ability to concentrate and memory to decline. Constantly ‘bathing’ in stress hormones also leads to, for example, a decrease in sleep. Makes sense, right? It may take a long time before it affects your daily life, but by that time, it’s likely too late.”

“So there I sat in my chair. My body and brain worked together and started a strike. It took 1.5 hours before I got up from my chair. Thank goodness I didn’t have waiting patients. Despite this experience, I kept trying to continue working. It didn’t work. Everything that had worked before, picking myself up and carrying on, simply didn’t work. Sick leave was the only option. The first month, I sat in a chair. Buying a carton of milk at the store 200 meters away was a day-long project.

The brain and nerves can recover and regrow, but it takes time. A lot of time. Some functions may never come back. Studies show that the response to stress affects the years that follow. What helps are meditation and physical activities in the right dose. Both activities calm the brain and reduce stress levels.

To help my recovery, I called a therapist and a doctor. The doctor’s task was mainly to evaluate me and approve my sick leave. Medication was irrelevant. Many people in similar situations experience mood swings, depression, and anxiety. However, this condition and fatigue differ in brain chemistry. They rarely occur together. Not in my case. The pleasure in life is there, and I have felt no fear.

How could this happen? Of all people, I should know this. My therapist said in one of our first meetings that my brain works the same as others. ‘No,’ I said as a half-joke. But looking back, it’s not surprising that my brain eventually went on strike. I had more or less every hour I was awake active stress. Receptions, meetings, courses, administrative work, supervising others, traveling to and from work, household chores, gardening, cooking, washing dishes – all kinds of activities. Like others, my life doesn’t go according to plan. At least the practical moments, sickness, and death, show up without warning. Time is running out, and everything comes to an end.”

“The level of stress hormones never gets a chance to fully recover. And to save time, I never gave them a chance to recover. Weeds grew in my garden. My food became very basic. The potted plants had died years ago. Last year, before I took sick leave, I couldn’t even listen to music in the car. My brain clearly indicated that it couldn’t handle any more stimuli.

A while back, in 2008, a colleague drove me to the Emergency Room because my heart was racing. There was nothing wrong with my heart. It was stress and lack of recovery. I didn’t get sick and went back to work the next day. That’s what it’s like to be Superman. I didn’t realize that my strength was also my weakness. There is much to think about and write about concerning the underlying mechanisms of my behavior. Mechanisms that are in no way unique to me. But I’ll leave that question at this point.

Just over a year has passed, and my brain is slowly recovering. Right now, I’m kind of in between. I’m getting closer to returning to working life. To start, for my job, I will work 25% with training. No patients. It will probably take a while.”

This article was written by Niklas Nygren and is translated and published with his permission. You can find his blog here (in Swedish).

Share this important message with your friends on Facebook so more people understand what it’s like to live with burnout!

You can now also follow us on Instagram for more great stories, photos, and videos.